When the mothership doesn't want it

Oct 10, 2022You would think that after funding and supporting people to develop innovative new ideas, that the parent corporation would want to take advantage of launching them. Nope. Markets are full of concepts that didn’t fit the parent firm – either not consistent with their strategy or just too small.

The Xerox PARC story

In their fascinating book, Fumbling the Future, Douglas K. Smith and Robert C. Alexander describe one of the most vivid examples of a company that saw critical inflection points coming, invested to make sure that they were ready, and then failed to make the bold move to benefit from what they had created. As is described in the documentary “Triumph of the Nerds,” Steve Jobs was ready to share the vision created at Xerox Parc.

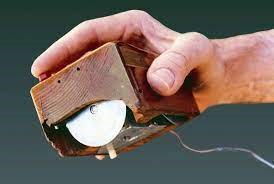

But as Malcolm Gladwell points out in his re-telling of the PARC story, the idea that Xerox didn’t see the potential of PARC’s inventions while Apple did is an over-simplification. If you look at the original mouse, invented in the 60’s at Stanford Research Institute, the mouse that PARC came up with and the mouse that Apple originally took to market, they are three radically different approaches to moving a cursor around a screen – as Gladwell points out, it was not so much stealing the idea as it was helping it to evolve.

The Engelbart mouse

Source: https://www.computerhistory.org/revolution/input-output/14/intro/1876

The PARC mouse

Source: https://www.techspot.com/guides/477-xerox-parc-tech-contributions/

The MacIntosh mouse

Source: https://madeapple.com/apple-macintosh-mouse/

The story that seldom gets told about PARC, however, is how a stubborn, highly creative guy by the name of Gary Starkweather created the laser printer which turned out to be a breakthrough product for Xerox. Even as Apple popularized computers for the mass market (not what PARC was set up to do), Starkweather was pursuing his vision of creating what we would recognize today as a laser printer.

Despite opposition from the mainstream corporation and its decision-makers, eventually Starkweather got to PARC, and with a small team created a working prototype. His bosses weren’t impressed – IBM was already in printers, and they couldn’t see how this idea would work. But, Xerox was already in machines that produced reams of printed paper – eventually, as Gladwell observes, “the thing that they invented that was similar to their own business—a really big machine that spit paper out—they made a lot of money on it.” And so they did. Gary Starkweather’s laser printer made billions for Xerox. It paid for every other single project at Xerox parc, many times over.”

Cisco, Webex and Zoom

A more recent story about an entrepreneur who had to leave the mothership behind is that of Eric Yuan and the creation of Zoom. Born and raised in China, Yuan reportedly was inspired to travel to America after hearing a 1994 speech by Bill Gates on this thing called the “internet.” In college, visits to his girlfriend involved grueling 10-hour train journeys, and he reportedly became intrigued at the idea of creating technology that would allow for virtual visits. He decided to move to Silicon Valley and applied for a visa. And applied. And applied. It wasn’t until his 9th try that he succeeded. He didn’t speak much English, but he did know how to code and in 1997 landed at WebEx, a startup in the videoconferencing space. WebEx grew rapidly, and was acquired by Cisco in 2007 for a price of $3.2 billion. He took a great job as the VP of engineering, in charge of collaboration software.

But all was not well. As Eric puts it in an interview: “As VP of engineering, I spent a lot of time meeting with customers, and found that most of them were not happy with the WebEx platform’s usability, reliability, and video quality. To me, unhappy customers are a sure sign of a failure. Frankly, I didn’t sleep well after I met with WebEx customers. I decided that the only way to solve the customers’ problems was to build a new, better video conferencing solution from the ground up. Cisco leadership didn’t want to make the necessary changes, so I founded my own company to build a solution from scratch.” That was in 2011. As he notes, “I was absolutely miserable at Cisco – I viewed Webex as my baby and had no control to impact the customer experience.”

Zoom today has revenues of over $3 billion, a market cap of close to $22 billion and the distinction of being used as a verb by hundreds of millions of people. Not that Cisco is exactly hurting – the company has a market cap of $165 billion and sales of $50 billion. So even if it didn’t take advantage of that particular opportunity, it seems to be doing just fine. Meanwhile, Zoom’s post-pandemic future looks challenging as competitors such as Microsoft catch up.

Orphan inventions

Of course, another reason that large companies don’t commercialize the inventions they fund is that the opportunity just isn’t material enough to make a difference to a multi-billion-dollar firm. Take the company Isoflux, which was founded by a Kodak scientist. It was based on novel technology, paid for and funded by Kodak, by David Glockner, with the permission of the parent firm! Today, it is a thriving little business with around $5 million in revenue, and a great reputation in its niche of specialty coatings. Good for Glockner, and not so terrible for Kodak either, as a $5 million opportunity relative to its 1993 revenue of $16 billion would not have been destiny-defining.

Innovation is cumulative

These stories reflect the reality that breakthrough innovations are relatively rare, and are often the consequence of years of tinkering and cumulative creativity. This is a point that is made by both Matt Richtel in his book on creativity “Inspired” and by Safi Bahcall in his work on “Loonshots”. This is why the story of innovation progress is so difficult to unpack, as it is never a straight line from concept to market-creating impact.

Meanwhile, at Columbia and Valize

I’m getting ready for my weeklong course at Columbia “Leading Strategic Growth and Change” in which we take a week to equip participants with the know-how to confidently pursue growth ventures and stare down uncertainty. Every day, we break for focused time to work on personal cases of the participants’ creation – it’s always an amazing experience. That’s happening the week beginning October 24 – this edition has a wait list, but we’ll be running the course twice in the Spring.

Our Valize SparcHub software has on-boarded our first couple of beta clients. It’s intended to help you align your strategy, your budgets, your project governance and how people move through the system. It’s the first app to embed the principles of discovery driven growth in software. Contact [email protected] if you’d like to see a demo.