The essential art of smart politics

Feb 28, 2022All too often, when we think about dealing with politics at work, it conjures up toxic and negative feelings. But if you want to make big ambitious changes happen, you’re going to have to get skilled at navigating the political waters.

When I say “politics,” what’s your reaction? If you’re like most participants I have in my Executive Education course “Leading Strategic Growth and Change” the very idea elicits a groan. People think of politics as invariably negative, involving hidden agendas, self-dealing, backstabbing and worse! And sure, it can take on those features, no question.

If you want to have an impact on an organization, however, I’m going to encourage you to consider an alternative perspective on politics. The way I think about it, politics are the activities you engage in to get people in your organization to do things that they wouldn’t otherwise do, absent your intervention. When you look at it that way, if your cause is just and you are on the side of the angels, politics is the essential mechanism through which you build alliances, create coalitions and get your ideas to come to life in the real world. Opting out is not an option. So, here’s an approach to working through your political situations.

A systematic approach

It can really benefit you to be systematic here. The approach I recommend has four key steps and a few additional considerations. The steps are:

1. Identify your goals from the political situation in specific terms.

2. Identify as many key stakeholders – individuals and groups – as you can. A stakeholder is someone who will be affected by the decisions made.

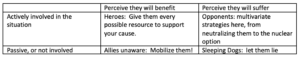

3. Political mapping – how active is each stakeholder with respect to the situation and how much they stand to gain or lose from it.

4. Strategize with respect to each category of stakeholder. Remember to use multiple prongs of influence as you try to get people to where you need them to be.

Let’s take each of these in turn.

Identifying your goals

It can help to take a page from the negotiation handbook to flesh out your own thinking. Try to be really clear about what success needs to be for this political situation. I suggest writing it down. “This situation will have been resolved to my satisfaction if A happens by B time while not costing more than C in money or D in social capital.”

Let’s say you are trying to get the green light for an innovation project. Your goal statement might be, “This situation will have been resolved to my satisfaction if I get the go ahead to spend $25,000 on a prototype by the end of the first quarter without losing funds from the rest of my budget or irritating Kim Dill.” It is also super valuable to lay out what the negotiation people call your BATNA – the best alternative to a negotiated agreement.

Identifying your stakeholders

Taking the time to map out stakeholders in your particular situation is always valuable, more so if the stakes are high. I’m always surprised then when I ask people who their key stakeholders are and I get a blank look. A stakeholder is anyone – person or group – that has a vested interest in the political outcome of your issue.

If you are in a company, typical stakeholders will be the kind of people who might be asked to fill out a 360 degree evaluation for you (subordinates, peers, superiors). They will be people who have control over budgets, decision rights over major topics (such as who gets to communicate with customers), and heads of key functions. Don’t forget whole groups, either, such as the people whose jobs will be affected by the outcome for you, as well as legal, finance, operations and other functional areas.

List in hand, now its time to assign each person or group to a quadrant in our political map.

Political mapping

The first dimension to consider is whether your particular stakeholder is likely to embrace your idea because they will benefit from it or resist it because they either will actually suffer or perceive that they will. And don’t assume that people are logical about this. People don’t live in your reality. They live in their perception of reality. This is a basic idea that a surprising number of people don’t understand.

Something that might double your company’s revenue and sounds like a no-brainer isn’t going to be embraced by someone who believes that their bonus will not be well served by that outcome. Similarly, something that seems just logical can be resisted by people who feel threatened by it.

The second dimension is how actively the person or group is in the effort. Are they in the mix, interacting, part of the conversations, or not. This is a little subtle because sometimes you will find you are having resistance from people who don’t seem to be active but who are very involved behind the scenes. These are often functional people, who in the service of doing their jobs may see what you are trying to do as undesirable or even dangerous.

Developing your strategies

Each of these categories of people need different treatment.

Heroes are people who support you. They think what you are doing is great, and you can count on them for backing. So where do we go wrong with heroes? We don’t nurture them, encourage them, give them the tools and resources to carry the message and make them look, well, like heroes! So don’t forget about people just because you think you can safely count on them for support. Check in, offer help, make sure they aren’t falling afoul of a political issue.

Allies unaware are a golden category of stakeholder. They would love what you’re doing but either they don’t know about it or don’t realize how great your success would be for them. Your challenge here is identifying and mobilizing them. Remember, sometimes some of the most important allies aren’t even in your focal organization. Future customers are a great case in point. People who would get jobs, new skills, more pay, better information or some other thing that they care about are all people who can be mobilized once you have identified them.

Sleeping dogs are less pleasant. Sleeping dogs are people or groups who are going to be worse off if you succeed (and let’s be honest, any big change will have winners and losers). The watchword here is, don’t wake them up until you have a strategy for dealing with the inevitable backlash. A bit of discretion about your plans with these groups does not go awry.

Opponents, of course, are the group that are likely to give you the biggest headache. Here, I recommend a sliding scale of strategies, in the form of a few questions.

1. Can you co-opt them? Sometimes we are so agitated by an opponent that we never even ask the question of whether there are things you can both agree on. A common enemy can be useful here. Apple and Samsung, for example, have no great love for one another in many of their businesses (and are waging an ugly battle in smartphones). But, they both can cooperate in competing against Google, a bitter rival.

2. If you can’t co-opt them, can you buy them off? This is more expensive. You’re going to have to give up something you want – budget, people, space, access, recognition – to gain their support. If what you are doing has an impact on another person or department, sometimes creating a power sharing / recognition sharing arrangement can be very effective. It can be worth it if the price to you is relatively modest and the benefit to you is substantial. So look for resources you might be able to offer that have that asymmetrical cost/benefit. And also don’t forget that the benefit to your opponent doesn’t just have to be work related. Perhaps you have access to some resource (backstage passes, tickets to the event, a personal meeting with someone cultural) that they don’t.

3. Can you get them to neutral? I mean, often, you don’t need them to be raving fans, you just need them to stop messing with you. If you can get them distracted on something else, worried about dealing with an even bigger problem than yours or more interested in another area of activity than continuing their arm-wrestling with you, that can move them to the neutral line. We use this all the time in competitive situations – you can make a move in a market that is hugely emotionally salient to your competitor which can lead them to stop interfering in markets that are important to you.

4. Can you create a coalition that is supportive of your idea and make your opponents’ resistance to it known? This is a little more politically tricky because you are asking other people to get involved and it will consume some of your social capital, but if they are going to benefit, it stands to reason that they will benefit as well from your being able to overcome the resistance. As Amanda Tattersall has found, sometimes fewer members in a coalition who can all agree on a specific goal (as opposed to many members who share a general goal but are not aligned on the specifics) are more effective.

5. Now we’re getting into more dangerous territory, because the next question is whether you can somehow isolate them from the focal situation. You are now getting right into the fray. A typical way this happens is that there is an appeal to a higher authority to resolve the conflict – and remember that higher authority isn’t going to be pleased to get dragged into it, especially if your opponent has a lot of political capital. As Ron Boire observes, “Another way this happens is to have your godfather call their godfather. This uses a lot of political capital but if you have a strong mentor that has influence over your blocker then it can be effective. Be careful though, you will need to bring gift… for both sides…’’

A note on power

Power matters in political situations. That seems pretty obvious. Power differentials are why so often, people with incredibly valuable information are ignored; why good ideas are overlooked and even why a solid mix of voices aren’t even part of the conversation. But what do we mean when we say someone has power?

I define it simply. You have power when you have control over a scarce and valuable resource. That could be formal power, as in control over raises, promotions or budget approvals. That could be informal power as in access to a respected inner circle of decision-makers or the possession of a great brand or stellar reputation. Power can also come from expertise and skill. The more invaluable you are to the organization, the more likely people are to tread carefully around you.

A historical story

The story of how Lyndon Baines Johnson got voting rights passed in the American Congress is illustrative. As told by his biographer, Robert Caro, Johnson was a genius at finding common ground between warring factions to drive the outcomes he wanted. Desperate to pass civil rights legislation once he had accumulated power (and after 20 years of refusing to support it in order to gain that power), Johnson had to figure out how to get enough votes in the Senate to get it through. Because of the Senate’s filibuster rules, his opponents needed only 33 votes to kill it (sound familiar?). Southern states have 22 senators and if you add in the senators from the Midwest and conservative Republicans, you don’t have to try hard to get to that number.

After trying (and failing) to get enough votes for months, Johnson finally went off to his ranch. Many thought he had given up, but what he was actually doing was figuring out a political strategy. He basically wrote off the southern senators. But he realized that senators from the Midwest and Rocky Mountain states at the time (1957) had no Black populations to speak of. While they had never been for civil rights, they weren’t dead set against them. In fact, it was an issue they didn’t care about much at all.

So what might they care about that could cause them to join with him to support civil rights legislation? It turned out that a substantial group of these senators had been trying to get dams built on the Snake River that runs between Oregon and Idaho that would have been a source of cheap electrical power to most of the Rocky Mountain states. They also would provide navigation by water, creating competition for railroads which operated in near-monopoly conditions.

It was, in many ways, a terrible idea and the senators had made very little headway with it. But, Johnson reasoned, if he could deliver them the dams (something their constituents cared a lot about) in exchange for their support on civil rights (something their constituents would barely notice), he might be able to persuade them.

He did get them the dams. They voted with him on civil rights.

And as in all things political, not every outcome is desirable for all parties. As we speak, in 2022, there are arguments dating back decades that the dams on the snake river degrade the environment, endanger the salmon and are harmful to the rights of indigenous people.

A last thing to remember is that politics almost always involves tradeoffs.